Brief Description

Students should be provided with a clear, measurable description of what they will be able to do, know, and/or experience as a result of having successfully completed the course. Learning objectives do so by defining what is to be learned by the student.

Definitions

The following will clarify terms you will often see in curricula.

Goals

Goals are broad, generalized statements about what is to be learned. Think of them as a target to be reached, or “hit.” They are too broad to be measured precisely. Instead, you need a number of learning objectives that support the goal.

Example: Students will gain an understanding of world cultures.

Course goals and learning objectives are not the same and are often interchanged and/or referred to incorrectly.

Objectives

Objectives are specific, measurable statements about what is to be learned. Think of objectives as tools you use to make sure you reach your goals.

Example: Given a sentence written in the past or present tense, the student will be able to re-write the sentence in future tense with no errors in tense or tense contradiction (i.e., I will see her yesterday.), with 90% accuracy.

If we think of a course module or unit as a bus, objectives tell students where the bus is heading. Course materials, content, activities, and tools support them during the journey. Assessments ensure they have reached the proper destination.

Measurable

Objective, specific criteria that any independent observer can use to determine if an objective was met.

Competencies

Competencies are specific applied skills and knowledge. They enable people to successfully perform specific functions. They are similar to goals.

Example: Possesses excellent grammar and writing skills, including the ability to write concisely, clearly, and logically.

Supporting Resources

ABCDs of Objectives

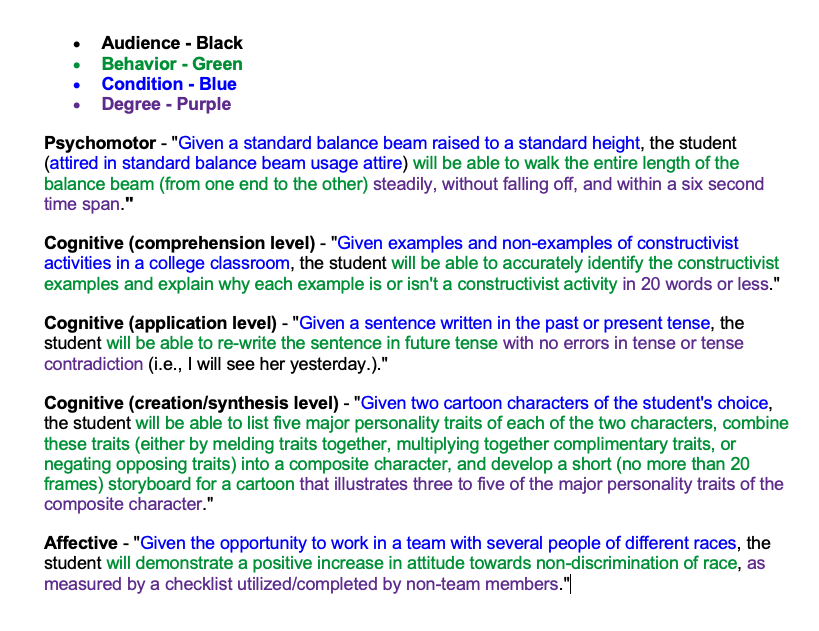

Objectives should contain an Audience (A), Behavior (B), Condition (C), and Degree of Mastery (D).

Example: “Given a sentence written in the past or present tense, the student will be able to re-write the sentence in future tense with no errors in tense or tense contradiction (i.e., I will see her yesterday.).”

- Audience – the student

- Behavior – will be able to re-write the sentence in future tense

- Condition – Given a sentence written in the past or present tense

- Degree – with no errors in tense or tense contradiction

SMART Objectives

Instructional objectives should be SMART:

- Specific – Use the ABCDs to create a clear and concise objective.

- Measurable – Write the objective so that anyone can observe the learner perform desired action and objectively assess the performance.

- Achievable – Make sure the learner can do what is required. Don’t, for example, ask the learner to perform complex actions if they are a beginner in an area.

- Relevant – Demonstrate value to the learner. Don’t teach material that won’t be used or on which you will not assess.

- Timely and Time Bound – Ensure the performance will be used soon, not a year from now. Also, include any necessary time constraints, such as completing a task in “10 minutes or less.”

Objectives are Explicit

Objectives should not be an assignment description, as the description may not be explicit enough for a well-written objective, and the assignment may encompass several objectives.

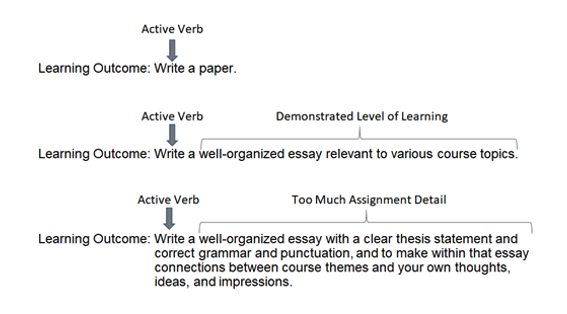

Here is an example of a goal for which a learning objective was written incorrectly.

- Goal: Write a paper.

- Poorly-written Objective: Write a well-organized essay with a clear theses statement and correct grammar and punctuation, and make within that essay connections between course themes and your own thoughts, ideas, and impressions.

(Adapted from Simunich, Gregg, & Ralston-Berg (2024); Adapted from Kheiry, Tarr, & Jerolimov, 2011-16)

This poorly-wrtten objective could serve as an assignment description (it would need a bit more clarification) or even a course goal, but it is not a well-written objective. For example, what does “well-organized” mean in this context? What are the elements of a clear thesis statement? Are there time constraints on the writing?

It would be better to break down this assignment into several learning objectives so all these things could be examined and clarified. Then perhaps the assignment could be tweaked to better align with these objectives.

Objectives Should be Explicit, but not an Assignment Description

(Adapted from Simunich, Gregg, & Ralston-Berg (2024); Adapted from Kheiry, Tarr, & Jerolimov, 2011-16)

Action Verbs

These are verbs that are often used in learning objectives. They are observable. You can find lists of action verbs in the following:

- Bloom’s Original Taxonomy (1956)

- Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy (2001)

- Fink’s Taxonomy of Significant Learning

Examples of Goals and Objectives

Examples of Goals

- Students will learn the basic principles, procedures, and objectives of using analytics to assess digital marketing communications.

- This course provides students with insights into both the science behind and examples of various leadership approaches, theories, styles, and techniques.

- Students will clearly and persuasively communicate their ideas.

Examples of Well-written Objectives

Below are some example objectives which include Audience (A), Behavior (B), Condition (C), and Degree of Mastery (D). Note that many objectives actually put the condition first.

When reviewing example objectives above, you may notice a few things.

- As you move up the “cognitive ladder,” it can be increasingly difficult to precisely specify the degree of mastery required.

- Affective objectives are difficult for many instructors to write and assess. They deal almost exclusively with internal feelings and conditions that can be difficult to observe externally.

- It’s important to choose the correct key verbs to express the desired behavior you want students to produce.

Typical Problems Encountered When Writing Objectives

| Problem | Error Type | Solution |

| Too vast/complex | The objective is too broad in scope or is actually more than one objective. | Simplify/break apart. |

| False/missing behavior, condition, or degree | The objective does not list the correct behavior, condition, and/or degree, or they are missing. | Be more specific, make sure the behavior, condition, and degree is included. |

| Only topics listed | Describes instruction, not conditions. That is, the instructor may list the topic but not how he or she expects the students to use the information | Simplify, include ONLY ABCDs. |

| False performance | No true overt, observable performance listed. | Describe what behavior you must observe. |

Course-level Objectives May Be Predetermined

Course-level objectives may actually be course goals, and be set by the institution with no option for faculty to change or improve them to be more measurable. In this case, focus on writing unit and module-level objectives. Providing measurable objectives at the unit and module levels clarifies your expectations for students and guides their work in completing the unit or module.

Alignment of Objectives With Course Materials, Activities, and Assessment

Alignment occurs when objectives are clear and measurable; course materials, activities, and tools support student success in meeting these objectives; and assessments measure the mastery of objectives. All elements of the course are designed and purposefully included to “align” and support the objectives.

Reeves states: “The success of any online learning environment is determined by the degree to which there is adequate alignment among eight critical factors: 1) goals, 2) content, 3) instructional design, 4) learner tasks, 5) instructor roles, 6) student roles, 7) technological affordances, and 8) assessment.” (Reeves, 2006, p. 294).

A well-written objective will assist you in aligning the objective to activities and assessment.

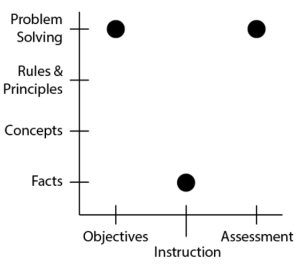

The chart below (Adapted from Dwyer 1991) shows a mismatch of the objectives, instruction and assessment.

In this case the objectives, instruction, and assessment were mismatched:

- Objectives were set to problem-solving.

- The students were assessed with problem-solving.

- However, only lower levels of learning, such as facts, were presented to students in lessons and activities.

Because of this students who have not been exposed to problem-solving techniques related to the course will more than likely have low-achievement when working on problem-solving assignments or problem-solving questions on an exam.

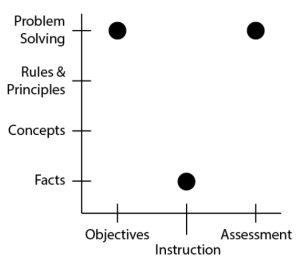

In contrast, the chart below (Adapted from Dwyer) shows one example of matching your objectives with instruction.

To match the objectives, instruction, and assessment, one would:

- Set your objectives to teach problem-solving.

- Design your instruction and learning activities to teach or demonstrate problem-solving.

- Assess the students at the problem-solving level.

Prominent Location for Goals and Objectives

- Syllabus – Course goals and course-level objectives

- Unit – Unit-level objectives

- Lesson – Lesson-level objectives

Additional Resources

- More about Goals and Objectives: General Goals and Explicit Objectives

- Bixler, B. (2018). Instructional Goals and Objectives.

- Action Verbs for Writing Objectives –

- OL 3400: This is a course on online course design periodically run by Penn State World Campus Faculty Development.

References and Resources

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (Eds.). (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. New York, NY: Addison Wesley Longman.

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives, handbook I: The cognitive domain. New York, NY: David McKay.

Dwyer, F. M.(1991). A paradigm for generating curriculum design oriented research questions in distance education. Second American Symposium Research in Distance Education, University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University.

Fink, L. D. (2013). Creating significant learning experiences: An integrated approach to designing college courses. John Wiley & Sons.

Reeves, T. C. (2006). How do you know they are learning? The importance of alignment in higher education. International Journal of Learning Technology, 2(4), 294-309.

Simunich, B. Gregg, A., & Ralston-Berg, P. (2024). High-Impact Design for Online Courses: Blueprinting Quality Digital Learning in Eight Practical Steps. Routledge.

This resource was created by Penn Ralston-Berg, Amy Kuntz, Donna Bayer, Danielle Harris, Brett Bixler, and Renee Ford. For more information about our quality standards, see Penn State Quality Assurance e-Learning Design Standards.

Page Contact: Penny Ralston-Berg